Who were Mao’s Red Guards? Where did their cruelty come from? One of them tells his incredible story

On the morning of the day Wang Jiyu crashes a wooden club into the top of someone’s skull, he eats a steamed bun. He slips into the military uniform he stole off a clothesline and trims some beard hair with a knife. Not bad, he thinks as he checks his face in the mirror, so young and already a guy. He is 16 years old, he has never kissed a girl before. He looks out of the window, a summer day, humid and overcast, the swallows circling low in the sky. It is 5 August 1967, a day in the middle of the Cultural Revolution.

For decades, Wang Jiyu has tried to block out that day. He has thrown himself into business, he has travelled and enjoyed himself, he has done what most of his generation do and what the government also asks them to do: he has tried to forget. Sometimes he sat together with his companions of that time. Was that a long time ago, they would assure each other, laughing a little too loudly.

But all at once that face reappears before him. The face of the other. Big eyes, high nasal bone. Wang remembers the feel of the club in his hand. Hears his own voice say, „I’m going to beat you to death.“

The memory comes when he is falling asleep, driving a car, or when he is sitting at a festively laid table looking into smiling faces. The other person looks at him and Wang knows: I am guilty. And when he asks around among those who are as old as he is, he suspects: I am not alone in this feeling. Memory lurks behind the glittering façade of the new China.

The Cultural Revolution is not gone just because it has passed. It has shaped an entire generation. Its gestures, its language, its sensibilities. And this generation is in power today. The memory of the Cultural Revolution stirs up many feelings, contradictory feelings, but almost no one speaks them out.

Wang Jiyu, 64, sits on a sofa in his stud farm near Beijing. It’s an idyll no one would expect to find so close to the capital. The chain of scented mountains rises in the background, the wind plays with leaves on the poplars, a pale-coloured horse walks on a harness, it is a Westphalian, imported from Germany. No sign points to this place, the entitled know the way even as it is. Wang has the appearance of a leader, what one would call in Chinese qizhi . Posture, demeanour, charisma. He speaks the jaggedly rolling Beijingese of the official’s child. He narrates as precisely as a surgeon makes his incisions. He will laugh in places that are not funny, you sense, so it is easier for him to tell the cruel.

There’s a television interview with him, he’s crying. There’s a man sobbing who was driven out of crying from an early age. Who was brought up to be a fighting machine.

On 5 August 1967, Wang Jiyu meets with his friends. With his gang. He always meets with his gang, what else can he do? They ride around on stolen bikes, they steal everything except money anyway. „We told ourselves that the others were enemies of the people. We weren’t just stealing, we were fighting capitalism,“ he will say later.They smash windows, kick signs, drill holes in melons and pee in them, hoping someone else would eat them. „There were about 20 of us kids, we wore dirty uniforms, our shoes stank. We kids had nothing to eat, so we stole. Our parents were devastated, they had been finished off.“ Wang’s parents, two staunch communists, are criticised and exiled to the countryside, like so many officials in the Cultural Revolution. The school has closed. Wang and his friends are left to fend for themselves.

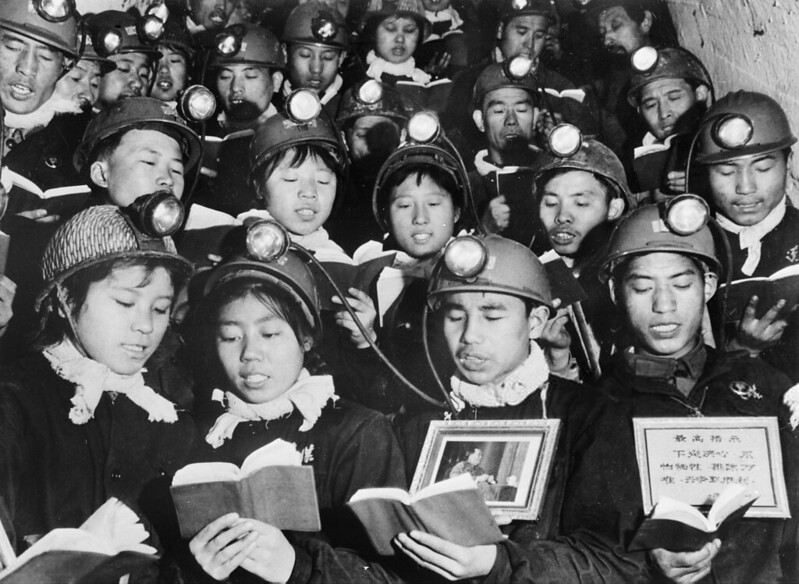

They are Red Guards. The soldiers of communism, the soldiers of Mao. They are civil servants‘ children, soldiers‘ children, raised in an airbase in the middle of Beijing, they belong to that generation from which the party leadership wants to forge the new China. „My upbringing was as red as it could be.“ Every morning, the teacher makes the children run across the sports field and says: „You will spread the world revolution. You will run to Asia, Africa, Latin America to bring the revolution.“ Wang runs and imagines himself liberating the world. He wants to be a hero. Fighting the enemy, the US. „Our upbringing was about hate. It was always about wiping out the enemy. Capitalism, imperialism. We were fed on wolf’s milk.“ Chairman Mao is everything to him.

Even today, knowing what Mao has done wrong, Wang finds it impossible to scold him. It would feel like an insult to his majesty. No, he says, „it’s just not my place.“

After the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, Mao drives his people from campaign to campaign. He is more radical than Marx and Lenin ever were, he wants more than revo- lution, he wants permanent people’s war. He believes that revolutionary zeal can achieve everything, but for this the revolutionary spirit of the individual must be honed again and again: in struggle. The Great Chairman is constantly making new enemies, one campaign taking over from the next. In 1958, Mao wants to transform his country into an industrial nation overnight, as it were, through the Great Leap Forward. Practical objections mean nothing to Mao; his adventurous economic policy triggers a famine that kills at least 20, but more likely 40 or 50 million people.

Mao is therefore sidelined politically, the technocratic reformers around President Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping are gaining influence. The Great Chairman feels increasingly isolated. He complains that Deng Xiaoping treats him like a corpse at a funeral. He respects his reputation but does not care about his views.

The Great Chairman wants to return to power and seeks allies outside the party: the boys, who are devoted to him because of the carefully cultivated cult of personality. He calls them to rebellion: against traditions and authorities, against parents, teachers and leaders.

In the final analysis, this is Mao’s way of preparing for the overthrow of the government of Liu and Deng.

In 1966 Mao declares the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, it will last ten years. „Smash the old, bomb the headquarters“ he orders his Red Guards. And gives them his favourite quote from the Dream of the Red Chamber, a classic novel: „He who is not afraid of being hacked to death with a thousand cuts will overthrow the emperor.“

Of course Wang Jiyu wants to become a Red Guard, everyone does. You don’t have to fill out a membership application or take an oath to do so, all you have to do is paint a poster with a slogan like „Smash the old world“ and you’re on the side of the revolution. The side of the winners. And no one dares to stop the Red Guard Wang any more. „We walked the streets wide-legged and proud, thinking ’screw you all‘,“ Wang Jiyu says today.

In the name of revolution, the Red Guards beat their teachers, destroy millennia of cultural property, humiliate, torture all those they declare their victims. Sometimes they kill them with their own hands, sometimes they drive them to suicide. In the „Red August“ of 1966 alone, 1700 people died a violent death in Beijing. But although the Red Guards pursue a common goal, they fight each other first and foremost. The movement has split into different groups that are at enmity with each other, each believing that they represent the true revolution.

„Once, right at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, we were arranged with another group in a meadow for battle.“ They are prepared. Have put on leather boots. „Because they make that sound on skullcaps.“ They set about one at a time. „My friends started stomping on his head with their boots. Bang-peng-peng, the noise got louder and louder, I got scared, I shouted, ‚Stop it, he’s going to die if you don’t.'“ Then one of the taller ones takes him aside. „What kind of class consciousness do you have?“ He looks at him firmly. „Can’t you see that this person is scum? An enemy of the people?“

Wang doesn’t know what to say. Looks down at the ground. Ashamed. Is he on the enemy’s side now? No. He must be like the others now.

Wang runs off, towards the head of the man lying on the ground, who tries to protect himself with his arms. The first time Wang steps in, he is still afraid. The second time he feels lighter. The third time he is euphoric. All at once all anger gives way, he feels free, released.

The cultural revolution is advancing. Red Guards attack civil servants, teachers, sometimes their own parents. One criticism session follows another, the enemies of the people have their arms twisted up for aeroplane position, they wear tall paper caps with invective written on them. They have to chant while being kicked and beaten, „we are the cattle ghosts and snake ghosts“ for example. The Red Guards loot trains that are supposed to transport rifles for the Vietnam War, they take weapons from the factories, they become army piles. The adults‘ power struggle has spilled over into the world of children and young people.

Wang and his friends, civil servant children used to privilege, call themselves „the old Red Guards“. They see themselves as veterans, the rightful successors of the Chinese Revolution. Now, however, their parents have been sidelined, and favour has fallen to those they once despised: the children of simple peasants and workers. The children of officials find this unbearable; they hate the upstarts, who in turn loathe the old privileged. Both camps form groups, the one of the civil servants‘ children is called „Alliance“, the one of the workers‘ children group „43“.

On 5 August 1967, the day Wang Jiyu beats a boy to death, hundreds of thousands gather in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. They demonstrate against President Liu Shaoqi and the reformer Deng Xiaoping, Mao’s arch-enemies. Red Guards invade the president’s residence and beat him black and blue. Two years later he will perish miserably in a prison hole, lying in his vomit and excrement.

In the afternoon, Wang cycles to the agricultural school, which has been closed since the Cultural Revolution and has become the meeting place for his gang. The friends are furious. They have just learned that one of their own has been beaten by the hostile Red Guard group 43. They swear revenge: „We’ll finish them off.“ Shovels, spades and hoes are stored in the school’s workshop. Wang thinks about what could best serve him as a weapon. He decides on a wooden club, a thick stick, 1.60 metres long, with a wooden square attachment at the end. They stand in a circle, weapons in hand, and repeat a sentence by Lin Biao, another of Mao’s designated successors, whom Mao later had killed: „When we hear the shot, we will go to the battlefield. And today I will lay down my life on the battlefield.“ That is their motto. Another is, „Blood for blood, life for life.“

„It was then,“ Wang Jiyu says today, „that the war really began.“

They wait, night falls. The boys of 43 have gathered in front of the school, they too hold spades, hoes and clubs in their hands. Wang and his friends step outside the door. A truck pulls up, men in blue overalls and helmets on the back of the truck, it is the reinforcement force of the 43. There are now 100 to 200 of them in total. They have surrounded Wang’s group, which numbers less than two dozen. „We were at our wits‘ end. In response, our foolhardiness grew immeasurably. It doesn’t matter if you’re young, small or weak, the stick in your hand is everything now.“

They line up. Wang lets his stick move from one hand to the other. He sees the men of the 43 running towards him, looks into distorted faces, they shout in chorus, „We’ll beat you to death.“

All at once the boy stands before him. It is only a split second, and yet he is struck by how handsome the other is. Slightly taller than six feet, thick eyebrows, the lip contour clearly drawn. He wears a helmet, holds a paving stone in his hand. He wants to smash it on Wang’s head, Wang feels as if it is happening in slow motion. He pulls his arms out in front of his head, the stone lands on his hands, the pain sears through him, it hurts so much that it makes Wang lucid again. He grips the club tighter. Hears his own voice say, „I’m going to beat you to death.“ He jumps as high as he can, lets the cudgel circle above his head, the other one flees, Wang runs after him. He lunges with the truncheon, hits the other on the head. His helmet flies off in a wide arc.

The other keeps running. Wang lunges again. The second blow hits him in the back of the head. The other flies to the ground, he looks as limp as a cloth bag all at once, rolls across the tarmac, remains lying.

Wang watches as he tries to get up. He is already propping his arms on the floor, „then I give him a third blow on his left forehead. I shout very loudly, ‚You’re not running away from me anymore.‘ I am exuberant. It’s a pleasure to hit a person.“

Blood on the tarmac, the other lies in it. Blood on Wang’s club.

Cries of joy reach his ear; they are the voices of friends. „We won!“ One shouts with pride, „We have slain one of them.“

„I cringe when I hear this. I ask, who has slain someone here? They say, ‚Well, you.'“ He looks around. City, faces, summer night. He thinks, „It can’t be.“ He closes his eyes, opens them again. Everything is the same as before. „Then I realised that I had committed the greatest sin a person can commit. Anyone who does that will end up in the 18th hell. The last, the deepest, the blackest.“

They carry the body to the infirmary. On the night of 5 August 1967, Wang Jiyu stands in front of a hospital couch. On it lies a boy. Blood blisters on his neck and lip. Blood oozes from a wound in the artery. Blood is pouring out of his mouth. The boy is still breathing out, but he is no longer breathing in. His eyes are half closed, his pupils wide. Again Wang thinks to himself: How good he looks. Zhang Youhao, 21 years old. The child of simple workers.

Wang grabs the doctor’s arm, clutching it so tightly that she cries out. „Can he still be saved?“ he asks. She brushes his arm aside. „Let go of me,“ she says, her voice cool.

„There’s nothing more we can do for him.“

From that moment on, the two boys belong together. From this moment on, Zhang will never let go of his killer.

After Wang beat him, another stabbed the victim in the neck with a spear, and a third gave him more blows. They were three killers, Wang Jiyu being the first. His blows alone would have been enough to kill Zhang, the prosecutor later declared: „You are the main culprit.“

For the next month, Wang Jiyu hides at home, his hair going out in clumps. „Before going to sleep, I think: I am a murderer. When I wake up, I think, I am a murderer.“ One night a woman appears to him in a dream. She is very tall, wearing a white, transparent robe, smeared with bloodstains. He cannot see her face. He is lying on a wooden board, there is no pillow or sheet, the board is unbearably hard. He wants to get up, but he cannot move. He hears her say, „You will lie here for 10 000 years. Ten thousand years.“

Wang wants to leave and decides to go to the Vietnam War. He takes the train south, looks out the window and sees fighting all over the country. Red Guards fighting Red Guards, youths fighting youths, children fighting children. On the island of Hainan he visits a naval hospital, inside lie three dead people who, as passers-by, were accidental victims of the Red Guards‘ street fighting. A little girl who wanted to sell sugar cane. An old farmer whose head was cut into pieces. A cadre from Dalian.

Wang is rejected as a soldier. He writes a letter to his parents, „I want to go back to Beijing. I have a confession to make.“ The letter seems to have been intercepted; on 14 December, soldiers stand outside his house in Hainan to arrest him. Wang is relieved, he longs for punishment, „If the law doesn’t punish you, your heart will.“ He spends nine months in a Beijing prison, then comes for re-education, but that is not enough for him.

„It wasn’t punishment, it was just a bit of decoration.“

He tries to forget. Business, family, pleasures, adventures. For a while it succeeds. Wang, a businessman in the south of the country, almost doesn’t think about back then. Then he turns 50 and suddenly fear creeps up inside him. He suffers from nightmares. „I think almost everyone who has done something wrong is caught up with it at 50. Suddenly the memory is there and you can’t do anything about it. The conscience checks in every second.“

Year after year, Wang burns death money for Zhang Youhao. Looking into the flames, he says to him, „Zhang Youhao, can you forgive me? If you do not forgive me, I cannot forgive myself. If you do not forgive me, I will remain in your debt all my life. I must bear the pain.“

The friends say, „Those were the days, everyone has dirt on them. Let go already.“ But he says, „Not everyone has become a murderer.“ The friends say, „Pray, believe, confess.“ But he says, „Religion is no way out.“ He wants to turn himself in to the police again, but the statute of limitations has run out on the crime. No earthly judge he can go before. The government explains that the Cultural Revolution was bad, but it was mainly the „Gang of Four“ that was to blame, and they are gone now. Mao was 70 per cent good and 30 per cent bad. The government wants to solve the catastrophe in a mathematical formula.

It is not forbidden to talk about the Cultural Revolution, the only question is who does it and how. There are no outspoken rules of censorship in China, which is precisely what makes it so tricky. Arbitrariness and fear still rule, another legacy of the Cultural Revolution. And don’t many people prefer to repress? In a country where victims still live alongside perpetrators, where even children once betrayed their parents? Forget, best forgotten, always ahead.

Wang couldn’t. He had to write down his guilt. A public confession. „I am guilty of killing a human being,“ is the title of the manifesto he wrote for three years. „Don’t do that,“ his wife had warned, „you’ll only get yourself into trouble.“ Five years ago he published his manifesto, it is the first public confession by a Red Guard. A few have since followed suit. Students who abused their teachers. A boy who denounced his mother, sending her to her death.

The uncle of his victim Zhang Youhao told Wang from the family, „We will never forgive you, but we respect you. You confessed.“ Since he did it, Wang says, he feels lighter. Zhang Youhao still appears to him in dreams, but Wang has accepted that he will remain part of his life forever. He has only one thing left to do: live with him. „I refuse to forget. I don’t believe in gods or spirits. But I do believe in the power of truth.“

He looks out of the window. On the horizon, the mountains of fragrance spread out. A row of poplars rises in front of it. The wind plays with their leaves, white and green.